Intro

“Agile habits” may sound like an oxymoron. Our central operating mode is autopilot—in other words, habits—because the brain is trying to conserve energy. On the other hand, we want to respond to change continuously. So how do our habits help or hinder us in putting people first, and creating value collaboratively?

It turns out it depends not only on whether you are aware of your habits, but also on whether you know how to break a habit into its components so that you can change the behaviour. Habits are central to behaviour change.

The Habit Loop

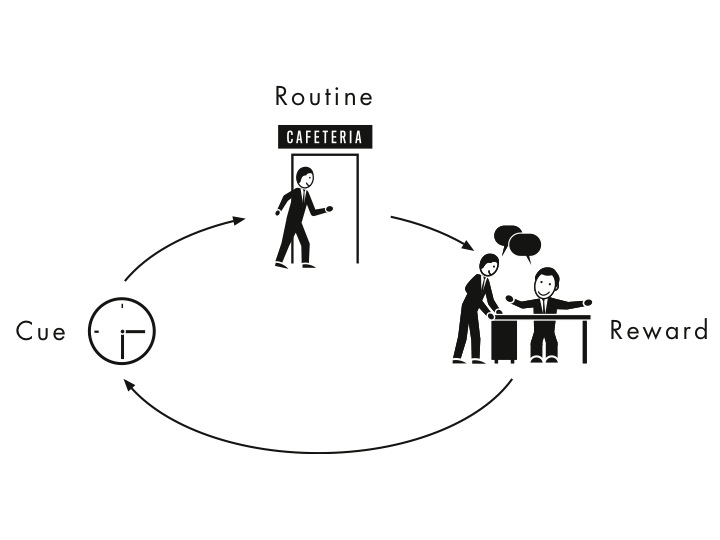

As Charles Duhigg explains in his book The Power of Habit, the habit loop consists of three parts: When I see [CUE], I will do [ROUTINE] in order to get a [REWARD]. Cues are often related to location, time, emotional state, other people, or immediately preceding action. Routines can be anything physical, mental or emotional, ranging from simple to complex. Rewards can be food or emotional payoff, such as promotion, for example.

The three parts of the Habit Loop: a Cue, a Routine and a Reward. Image Credit: Charles Duhigg.

It’s the craving (desire) for a reward that drives the habit loop. And you’re probably not even aware of what that craving is. What makes it even more challenging is that habits (good or bad) never truly disappear as they’re encoded in the brain, driven by the craving, and waiting for the right trigger: the [CUE]. Forming a new habit begins with a new craving.

Changing A Habit

Repetition is a form of change: you get what you repeat. As a habit is something you do repeatedly, changing it requires changing the [ROUTINE] component in the habit feedback loop: in other words, the behaviour that happens between the [CUE] and the [REWARD]. Once you’ve identified the [ROUTINE], you’ll need to look hard for the [REWARD] you’re craving. Next, you’ll want to isolate the [CUE] that triggers the habit loop. After these steps, with your new awareness, you’re hopefully ready to make a plan for your new, improved routine, and commit to it—until it’s time to change it again.

Sounds easy? It’s not. You’ll also need to believe you can change. Change is social, and your behaviour is shaped by other people and the environment. You can’t rely only on your willpower or your good intentions. Building habits that are easy to do increases your chances that you’ll actually do them. (Remember, the brain tries to save effort!) Could it be that the fear of change is mostly about the fear of losing the reward? If we frame the habit change as creating an alternative (and easy to do) routine to the same or similar reward, change can become much easier. And that’s the key. The change only becomes real if it becomes part of who you are: your habit.

The Agile Ecosystem

What does all this have to do with being agile? Everything. Responding to change requires you and your organisation to be aware of your habits and the habit loop, so that you can inspect and adapt your routines. You need a good system and a supportive environment to make progress, because we humans often fall for instant gratification.

You do not rise to the level of your goals. You fall to the level of your systems.

There’s nothing wrong with running on autopilot (without our hundreds of habits we’d soon become mentally paralysed). We’re building on our automated habits to save energy for more advanced activities. It becomes problematic only when the habit is destructive, or when we’re just mindlessly repeating the habit, stopping to uncover better ways. That’s the road to mediocrity at best—and your customers/audience will take notice.

Here are some examples in agile context:

- People first: Working from the office is a habit. Try working remotely, and see if the flexibility of distributed teams improves your effectiveness (spoiler alert: Yes, it often does).

- Delivering value early and often: Creating value consists of a collection of organisational habits that help deliver what your customers need and want. Not sure if you’re creating value anymore? Try new routines for interacting with your customers/audience. Or is your continuous delivery pipeline not supporting your desired pace of change in the product? Are you struggling with a slow Time-To-Market? Fix your pipeline! You need to slow down to go fast.

- Collaboration: Facilitating meetings is a habit. Tired of the “Big 5” (presentations, managed discussions, status updates, brainstorming and open discussions)? Try some Liberating Structures.

- Adaptation: Is your autopilot habit not bringing you enough bang for the buck? Time to fine-tune your routine again!

Two great books: Atomic Habits by James Clear, and The Power of Habit by Charles Duhigg.

In Closing

The role that habits play in an agile organisation is an underrecognized topic. I can highly recommend two books if you want to dig deeper into the power of habits (as you probably should if you want to uncover better ways): Atomic Habits by James Clear, and The Power of Habit by Charles Duhigg. I’m only scratching the surface here, but having a better understanding of how habits work has been very valuable on my own journey as Scrum Master and mindfulness enthusiast.

Don’t be a victim of your habits. Becoming better at the external agile feedback loop requires you to become aware of your — and your organisation’s — internal habit feedback loops. Choose your habits wisely, be mindful of the habit loop, and review and fine-tune your routines often. Thanks for reading, and good luck in improving your agile habits!